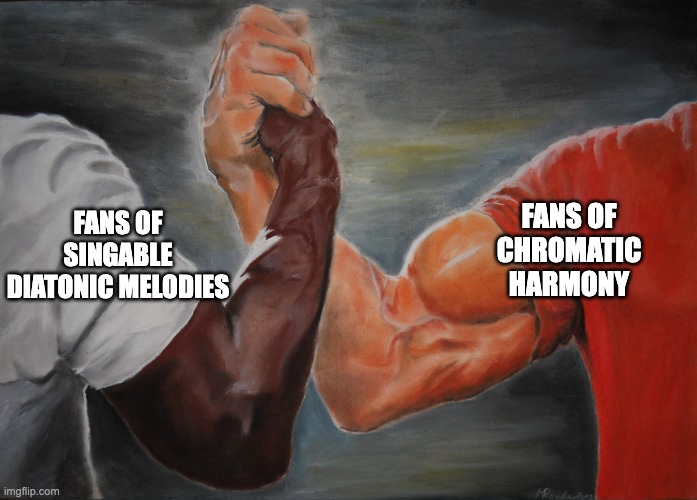

The early stages of learning music tends to leave musicians with the impression that being “in a key” means using notes in the key’s signature scale; the “diatonic” notes and chords built from them. Nope! Lots of chords using chromatic notes sound totally natural when in a key because…

A key is not its scale.

A key is more like a mental state set up by a particular chord being perceived as “home”. This provides a context where some melodies and harmonies sound more natural than others.

How do we get into this state? We think it’s from having the chord first in a piece or a loop, or by giving its chord tones emphasis by some melody. For example, here are the critical notes (root and 3rd) of a G major chord with the G note doubled on top, and we give G a little jump from D to help it be heard as the tonal center:

Once established in our head, there becomes a variety of familiar harmonies we’re use to hearing, but it isn’t really about the G major scale.

An example 4 bar loop in G major

We have: G – C/E | Eb – C | Bø7/F – E | Am – Cm D7

The Eb chord in bar 2 (with Eb and Bb instead of E and B) sounds a bit intriguing, but not at all wrong:

And if you stop the song and play a scale over this chord, you’ll find it’s not the G major scale that sounds best!

It turns out the current chord has a ton of influence over which scale(s) sound best at the moment. Or as I like to think about it, some chords bend the scale to support the chord.

And this little part below from bar 3 doesn’t even sound like G major when you take it out of context:

This is plain old key of A minor material, even using the A harmonic minor scale with F instead of F#, and G# instead of G! In the context of our G major song, this is what’s called “tonicizing the two” because we’re momentarily using the dominant chord of ii (E), treating Am like a temporary tonic. But we’re still in G major.

So what can we play? And with what scales?

I put together a broad overview of chords commonly used in G major (and all the other keys). Any resource like this should be treated as a starting point, and I’m definitely not implying that music using more or rarer chords will be better in some way.

Regarding scales, to avoid perpetuating another misconception, we shouldn’t think of there being one “right” scale to pair with any chord. Context, genre, taste all come into play, and as with harmony, trust your ears. Usually the scale will have several notes in common with the key signature.

Of course there are some ways to predict scales that are commonly used… in another post.